Here’s a view of the first Winter Creek check dam upstream from Roberts’ Camp. Note the stair-step appearance of the inundated check dam. The larger dam’s footing is protected by the smaller sill dam in the foreground. In the great 1969 Flood, also an El Nino year, all the dams in the main Big Santa Anita Canyon, downstream from the confluence of the North Fork, lost their sill dams in just one evening. Sadly, ten cabins also washed away.

Here are some photos I took of the Big Santa Anita Canyon ten years ago when Southern California experienced its’ last significant El Nino fall & winter. Wrightwood & the Big Santa

Our hiking trail (Gabrielino) washed out at this bend in the canyon between Cascade picnic area and Sturtevant Camp. The painstaking process of building a low wall for fill sand has just begun. My wife Joanie & I were running Sturtevant’s at the time. Our rain gauge had recorded over 90″ before the season was through! Opid’s Camp, in the West Fork of the San Gabriel River, recorded over 110″ that same winter.

Anita are about 25 air miles apart from one another. It’s possible to hike (approx. 75 miles) between Wrightwood and where these winter images were taken out

This is a scene of the Big Santa Anita Canyon Dam, located just north of Arcadia, at maximum spill way. Over 1,700 cubic feet of water per second was running through and over the dam the day this photo was taken.

in the Angeles National Forest’s “front country.” What the two places share, of course, are the San Gabriel Mountains!

When warmish Pacific Ocean storms come in off the coast, it’s the front country that faces the San Gabriel Valley and Los Angeles Basin, that really gets slammed. You might say that our mountain rain is a text

book example of the orographic phenomena experienced on immeasurable mountain slopes. If the base of the mountain, L.A. for example, receives an inch of rain, 2000′ upslope you

might receive over two to three inches out of the same storm. The mountainous geography wrings out the clouds as you keep climbing up in elevation. As a rule, Wrightwood receives about a third of what the front country slopes might

Here’s a scene looking up canyon, near Roberts’ Camp, Big Santa Anita Canyon. Note the two cabins in the background. These dark trees standing in the tumultuous water are white alders. It is here that I decided to turn around and not continue up canyon. The stream becomes a wall-to-wall situation not too far ahead.

get. When it’s summer time, however, our proximity to the Mojave Desert provides us with thunder storms that the front country can only dream about. So both sides of the San Gabriels have their give and take when it comes to wet weather.

Big Santa Anita Canyon is not a large watershed at all, say in comparison to the San Gabriel

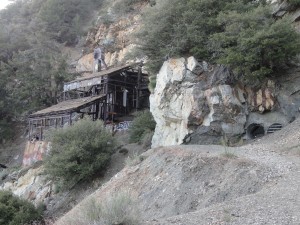

Looking back at the stream as it’s about to roll over the top of a check dam. These “check dams” were built throughout many of the Angeles’ front-country canyons back in the late 1950’s through the late 60’s.

River. Yet, it’s miles of steep terrain can become saturated after days of relentless rainfall. Generally, the “canyon” can take upwards of a dozen inches of rain over several days before the stream comes up appreciably. The El Nino storm systems of 2004-2005 sometimes came in one after another, barely allowing more than a half day of blue sky and no time for the moisture to percolate down through the fractured rocky slopes. These photos show what a front-country stream can become after multiple storms come through, one after another. What they can’t convey, is the deafening sound, so loud in some cases that it’s impossible to yell across a stream this size and be heard. When in a little cabin alongside a roaring stream like this one, it’s possible at night, to feel and hear the impact of shifting boulders, jarring up against each other in the dark froth. Scent is a also a highlight of canyons in flood stage. Organics

This is how high the streams in the front country can become during a heavy rain season. What you’re looking at is a check dam, approximately 50′ across in width. This kind of water is nothing to tangle with.

locked away in loamy soils along stream banks for years and years are suddenly released. There’s this olfactory collage of crushed and soaked bay leaves, oak leaves, decomposing vegetation and grinding rock that are seldom experienced in drier times.

by Chris Kasten

This poem by W.S. Merwin, entitled “Rain Travel”, seems to encapsulate the nocturnal in watery canyons, like the Big Santa Anita, during times like these.

“I wake in the dark and remember it is the morning when I must start by myself on the journey. I lie listening to the black hour before dawn and you are still asleep beside me while around us the trees full of night lean hushed in their dream that bears us up asleep and awake. Then I hear drops falling one by one into the sightless leaves and I do not know when they began but all at once there is no sound but rain and the stream below us roaring away in the rushing darkness”.

Here’s my bike in front of a slide that covered the road while I was photographing the Big Santa Anita during flood stage. Fortunately, my truck was sitting in a friend’s drive way in north Arcadia. A number of Forest Service employees had vehicles trapped on the upper end of this and other slides for nearly 10 months!