BIG HORN MINE

Total Trip Length = 3.6 miles round trip

Elevation Gain = 500 feet

Trailhead Location: Vincent Gap on the Angeles Crest Highway

This grouping of alpine wildflowers softens the sharpness of Mt. Baden-Powell’s north ridge while nearing the summit. Pine Mountain, Dawson Peak and Mount Baldy make up the skyline.

When it’s hot and sweltering in the front-country of the San Gabriel mountains, taking your next hike to Mt. Baden-Powell, located in the high-country near Wrightwood, just might be a good way to go. The views are spectacular and far-reaching under deep blue skies. There are few places where you’ll encounter such a variety of conifers. Earlier this summer, my wife and I hiked out to the abandoned Big Horn Mine. A couple of miles of hiking along a dilapidated dirt

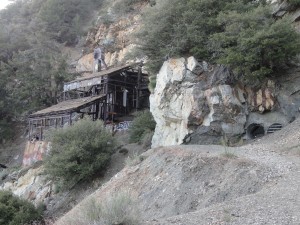

View of stamp mill and adit (horizontal mine shaft) clinging precariously to slope of Mine Gulch on Mt. Baden-Powell.

road that skirts the steep and, at times, forested mountainside of Mt. Baden-Powell, takes you to this historic relic of the earlier days of mining in the East Fork of the San Gabriels. The mine’s location was found by the back-country recluse and mountain man, Tom Vincent, back in 1895 while out hunting for big horn sheep. Various groups of investors and entrepreneurs each took their chances at developing the remote mountainside mine from the turn of the century up until the early 90’s. In all cases through out the decades, investment exceeded the value of the extracted gold, followed by diminishing returns until abandonment.

This narrow track that once carried ore cars is still looking pretty good. The Big Horn Mine is comprised of both horizontal and vertical shafts.

This pattern of running the mine for a some time, only to be followed by quiet idle years, has continued for over a century. Today the disintegrating remains and cool, empty tunnels sit quietly in the steep, rugged slopes of Mine Gulch at about 7,000′ in elevation.

To get to the mine’s trailhead, park at Vincent Gap on the Angeles Crest Highway, just west of Wrightwood, CA. Pass by the white pipe gate, continuing along the red, rutted old mine road. As you skirt alongside the mountainside, watch for a hiking trail switchbacking down into the Sheep Mountain Wilderness Area of Vincent Gulch and on into the expansive East Fork of the San Gabriel watershed. Pass by the trail turn-off, staying with the road as it skirts alongside a steep mountain chute,

Mt. Baldy and Iron Mountain as seen from within the steel framing of the Big Horn Mine’s stamp mill.

then enters into a soft and forested slope of mature sugar pine, white fir and the ever-present aromatic jeffrey pines. Eventually, you’ll leave the protection of the forested slope and enter back into steep and arid mountainsides of fractured rock, peppered with yucca, manzanita and mountain mahogany where these plants can get a toehold. In places, the road can be completely washed out, necessitating scrambling alongside narrow and crumbling scratch trails made by other hikers. The exposure and consequence of a misstep is a reality along this side of Mt. Baden-Powell, so take your time. For the most part, the hiking is fairly easy for good stretches, eventually taking you around a shoulder on the mountain to the Big Horn’s rusted out stamp mill and other assorted mining debris, pipe and concrete slabs.

The adits, horizontal mine entrances, are fenced off with steel bars; the last owner’s attempt to keep hikers from going into the mountainside. When you get to the end of the road, be careful crossing the steep slope over to the stamp mill. Return the way you came.

MOUNT BADEN-POWELL

Total Trip Length = 7.6 miles round trip

Elevation Gain = 2,800 feet

Trailhead Location: Vincent Gap on the Angeles Crest Highway

Mt. Baden-Powell, once known as North Mt. Baldy, was re-named for Lord Baden-Powell, founder of Boy Scouting in the United States. The approach to this 9,399′ peak is by way of the pleasantly forested north-east facing mountainside, affording you ample shade and stunning views out over the Mojave Desert and eastern high country of the San Gabriels.

Joanie Kasten stands at Mt. Baden-Powell’s summit. Pine Mountain and Mt. Baldy make up the backdrop as Old Glory flies in a brisk mid-summer breeze.

You’ll want to dedicate most of your day to this hike due to the high elevation of the summit and also some of the steep trail pitches between the 37 switchbacks. Bring plenty of water for each person in your group, i.e. two to three liters. Avoid taking this hike in the winter and early spring months due to steep, icy slopes that parallel this route. When there’s ice, the potential for a fatal accident is ever-present. During the warmer months, this well maintained trail is a wonderful route to the top and quite safe.

Head on up the red, dusty path alongside the split cedar fence. Scrub oak, white fir and jeffrey pines shade your route as you head toward the

A view from part way up a limber pine. Looking toward the north, you can make out the faint outline of the Pacific Crest Trail, PCT, as it parallels the left hand side of the ridge. Note the trail junction sign, where the trail continues on toward the west passing by Mt. Burnham, Throop Peak, Islip Saddle and on along the spine of the San Gabriel mountains. 2,200 miles further, the PCT terminates in British Columbia, Canada.

first of many switchbacks. The trail switches back and forth along the broad, northeast facing ridge line of the mountain. Each time the trail wraps back around the ridge, for quite a ways up, you can look back down at the Vincent Gap trailhead parking area, possibly even spotting your car. Four switchbacks up is a nice little wooden bench to rest on. By now, you can begin to gauge your progress, by sighting out across to West Blue Ridge, gradually gaining a greater view out into the Mojave desert’s vastness. Old, magnificent sugar pines begin to make their presence as you continue climbing up; their long horizontal branches terminating in clusters of long cones that exude bright, shiny sap. A large cool, flat slab of rock is up this way, too. The mountains internal coolness is often evident when laying up against this monolith.

This benchmark attests to Mt. Baden-Powell’s former namesake, North Mt. Baldy. Affixed to a boulder at the summit, it marks the high point (9,399′ elevation) of your day.

Almost half-way up, a wooden sign at the end of a switchback points the way to Lamel Spring, which makes for a tranquilly floral spot to take a rest. The switchbacks become ever broader from here, passing by inviting little flats filled with pools of shade and quiet sunlight where people have camped amongst the scented evergreens, perhaps taking in the glow of sunrises and sunsets not to be forgotten. A bit further on, the switchbacks begin to tighten up, as does the steepness. Lodgepole pines are now becoming the the dominant conifer, as you’re squarely into the 8,000′ + elevation range. The bare forest floor is in places littered with their tiny ornate cones. Glades of low buckbrush and deer brush fill in empty pockets where the perfectly straight lodge poles have left a little sunlight. On and on you keep climbing while converging ridges begin to make their way toward you and the ever-nearing summit. And then it happens – twisted and wind bent limber pines finally appear. At this point you’re nearly

The author takes a break at the base of a wind-sculpted limber pine near the summit of Mt. Baden-Powell, San Gabriel mountains, CA. At this elevation of 9,300′, the sky appears to be nearly cobalt blue.

9,000′ up and there’s a spaciousness between these ancient trees that in many cases are nearly as wide as they’re tall. The lines of the sun burnished wood of these rare trees appear twisted and deeply etched by centuries of sun, wind and ice. Not much further up, the switchbacks finally give out and you find yourself hiking atop a narrow ridge with a dizzying drop-off into the East Fork thousands of feet below to your left. Fortunately, the trail is just a few feet over on the gentler, west side of the ridge. Near the end of this airy ridge, there’s a tree near the Pacific Crest Trail cut-off and the final summit approach which is worth pondering. A weathered, wooden sign indicates that this limber pine is over 1,500 years old! There are other trees in the area that are reputed to be over 2,500…., yet remain unmarked to keep them protected.

A weathered brass tag honors the memory of a loved one. It was placed some years ago up on a limber pine, high atop Mt. Baden-Powell.

Soon you’re on top of the mountain. The top is rounded and exposed. A four-sided concrete and brass edifice to scouting, its’ base eroding, is near the top , along with an uncovered trail register with hundred of entries of hikers who made the climb. Look off in any direction and the view’s good. On clear, wind-swept days, you can make out distant peaks like Mt. Wilson and even the channel islands. Myriads of canyons drop off all around. Enjoy the return trip back.

Here’s a close-up of needles and accompanying cone on a limber pine, Mt. Baden-Powell, San Gabriel mountains, CA. Short needles are sheathed in clusters of five. The clusters of needles are concentrated at the ends of cord-like branches which withstand the very high winds that occur high on the mountainside.

by Chris Kasten